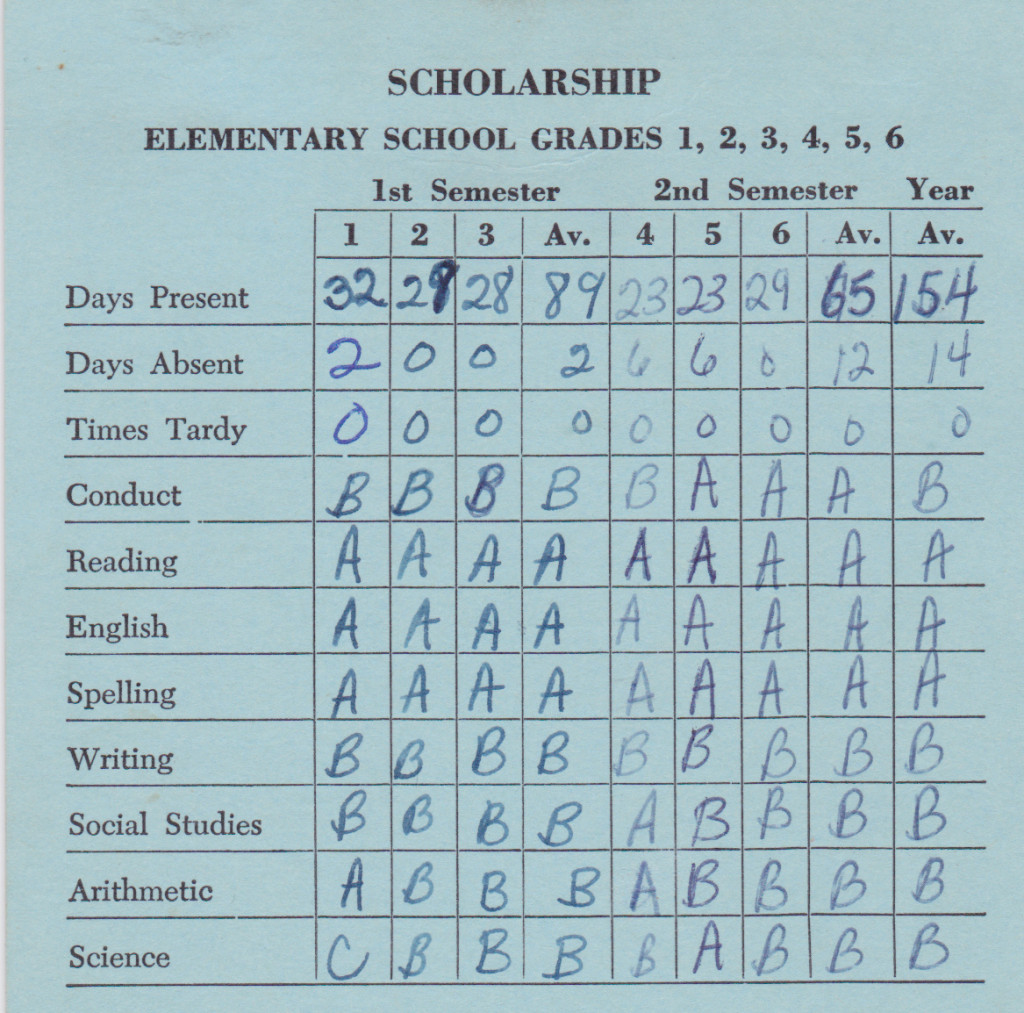

A Caregiver’s Report Card

Are you secretly giving yourself a grade for caregiving? Feel you’re falling short? Don’t be ashamed to say so, because I get it. Growing up in my house, a grade of “C” was equivalent to an “F,” and at dinner each night, my younger siblings and I had to come up with good answers to my father’s perpetual question, “What did you do of any consequence today?”

Decades later, while caring for both my parents during the last phase of their lives, and still putting myself to Dad’s test, these are the responses I finally arrived at.

Perfect solutions don’t exist when caregiving, and what may work one day, may not work a day, a week, or a month later. Even knowing this, we often drive ourselves to exhaustion processing tons of information, and absorbing solicited and un-solicited advice while trying to honor the hopes and expectations of the parent we’re caring for. It’s inevitable that sometimes “analysis paralysis” sets in. This happens when we worry about not having all the facts, are concerned the decision may be the wrong one, or have convinced ourselves that the worst possible scenario is going to occur. What can help is learning to stop second-guessing our decisions; remembering we can only work with what we know at any given time, and making peace with the idea of “acceptable for now.”

Caregiving is a verb, and our days run on multiple To Do lists – dealing with a deeply flawed medical system, particularly where the elderly are concerned; ordering and picking up medical supplies and prescriptions; filling out insurance forms; and responding to crises we’d rarely imagined. It’s never-ending, yet caregivers often feel they should be doing more. Once in awhile, try making an “Accomplishment” list, instead. Write down all the things you manage to handle while taking care of a parent/ a spouse/ a child/ a full time job/ a home/your own needs, or any combination thereof. Even you will shake your head in disbelief at what you’re achieving under great odds.

Try not to compare your caregiving experience with others. I was speaking with someone who’d been taking care of a father with dementia for over 10 years. When I commented on how hard that must be for her, she said, almost apologetically, that her dad was in a memory care unit, so she wasn’t a twenty-four hour caregiver. The reality is that caregiving is a 24/7 job whether your parent is with you or not. You’re still the one being called at all hours when issues arise and difficult decisions must be made, so don’t ever devalue your efforts.

Often, the toughest part of caregiving is recognizing that you can’t always make things better for Mom or Dad despite your love and efforts. And sometimes, being with a parent is more important than doing for them.

Finally, forgive yourself for being irritable, resentful and sometimes wishing your caregiving responsibilities were over. It doesn’t make you a bad person. It just makes you human. The irony is that accepting this fact can release some of the unrealistic expectations and pressure we put on ourselves to try and fix everything that goes wrong.

So, for those of you who still feel the need to grade yourselves, I’ve devised a new system with caregivers in mind.

A – Accomplished

B – Big-hearted

C – Compassionate

D – Dedicated

F – Fabulous

Now – go ahead and give yourself the “F” you deserve.