Awhile back I invited my writer’s group to compose a letter to people they interact with who are not caregivers themselves. To say the flood gates opened with this assignment would be an understatement.

Responses included:

The son or daughter who never calls, or who only calls to tell you about their problems. Or maybe they rarely visit, or never ask how you or your spouse is doing?

The busy sibling who has no time to help, yet is always happy to criticize your caregiving efforts.

Numerous acquaintances who use that well-worn phrase “Let me know if you need anything,” as a sign-off to every conversation, and that’s where it stops.

The well-meaning friend who comments on how worn out you look, just when you were feeling pretty good.

The doctors who act like you and your parents are working for them, and not the other way around.

It’s clear this particular prompt struck such a nerve, and in all instances the group remarked that they stifled their responses for fear of being labeled a complainer, a troublemaker, or a bitch. I get that keeping quiet can sometimes be the better plan, but, there are many instances where we’ve simply got to speak up, because remaining silent only reinforces a status quo which is hurtful to those we love, and to ourselves.

Here are a few excerpts from my own letter, written to some of the physicians involved in my parents’ care over the course of six years. This isn’t an indictment of all doctors, for some were compassionate, generous with their time, and truly seemed to understand the challenges faced by my parents, and me as their advocate. For the record, I gladly wore the labels noted above and did share a few of these comments with healthcare personnel.

______________

Dear Medical Professional,

Before we begin, please fill out this ten page form of very tiny type, documenting your qualifications. Already completed this for the last caregiver? Sorry, I’ll need you to do it all over again. You’ve been waiting to see me for an hour? Well, everyone knows that a 9 o’clock appointment really means 10.

Do not automatically assume that all patients in their late 80’s have no capacity to understand what you’re telling them. Also, be prepared to answer a list of questions about side effects, expectations of recovery, etc. after you propose a risky surgery or procedure. Never use the enticement, “You’re not paying for this. It’s covered by Medicare.” Where do you think Medicare gets their money?

Please refer to elderly patients as Mr. or Ms. or Mrs. and not by their first names, or as the UTI or cardiac cath in room 202. Surviving this country’s health care system thus far, entitles them to a great deal of respect, and you are treating a person, not a condition.

Stop saying, “How are we doing?” when a caregiver and her parent finally get to see you after sitting for two hours. WE are pretty damn tired of late night trips to the ER. How are you?

Don’t look at a caregiver and say, “You need to do such and such,” as if this person has been hanging out on the couch eating bonbons and watching soap operas, all this time. Instead, look her in the eye and ask, “And how are you holding up?”

The next time a nurse brings an elderly patient the two Tylenol you prescribed for pain due to a pelvic fracture, don’t get all huffy when the daughter/caregiver raises hell and demands to speak with another hospitalist. Prescribing opiates may not be your first choice, so do your research, or call in a pain management specialist. Just don’t minimize that patient’s distress.

To close, I get that you work long and demanding hours. As a caregiver, so do I. Maybe we can work together as a team to change things in this broken healthcare system of ours. Please accept these suggestions as a token of my commitment to this worthy goal. The next batch of suggestions will be accompanied by a bill for consulting services rendered. Payment will be due within 30 days, and FYI, I don’t accept insurance.

Respectfully,

Judith Henry

______________

Readers, if you’re game to give this exercise a try, pen your own letter to someone, and look closely at what you’ve written. Like the members in our writing group, you may feel a sense of relief just getting these unspoken words out of your head and onto paper. But think for a minute – is there a way to present your thoughts constructively to the person you’re writing to? For example, instead of automatically saying, “I’m fine” to the adult kid who calls with a cursory “how are you?” be honest. To the physician who barrels in with a treatment or surgery, assuming your parent (or you) will acquiesce quietly, explain you have a list of questions prepared to be answered first. When someone tells you, “Let me know if I can do anything,” don’t just say ok. Tell them what they can do to help, and be specific.

You never know. Your words may just start changing things for the better.

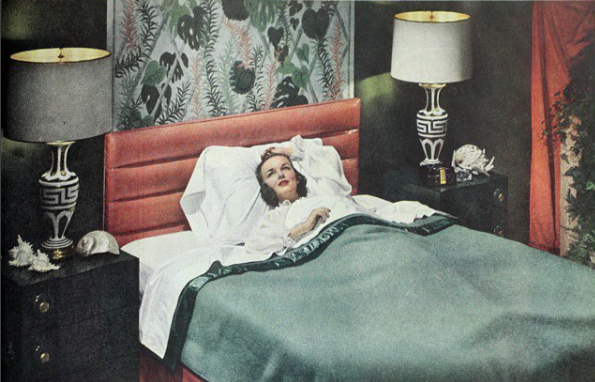

“Poppies” painting by my mother, Sally D

“Poppies” painting by my mother, Sally D